Pathway to resilience n ° 2: Preserving agricultural land

- 2020-02-01 09:34:30.0

- 14138

- farmland, soil, artificialisation

Habitats, roads and areas of activity (commercial, industrial or artisanal): human constructions are spreading at a sustained pace, often irreversibly destroying fertile agricultural land located near our places of life. To preserve these lands, and facilitate the relocation of production, communities must set a goal of “zero net artificialization”.

État des lieux

Farmland: a threatened common good

In France, the agricultural area has been declining for several decades. Today it represents about half of the national territory, or 28 million hectares, against nearly 35 million hectares in 1960. The main cause of this decline today is the artificialization of soils (Figure 15) , that is to say the transformation of natural or agricultural spaces into human constructions: dwellings, roads, gardens, industries, commercial areas ... Since 1981, it is estimated that two million hectares of land have been artificialized, the equivalent of twice the area of the largest metropolitan department, the Gironde.

Figure 15 : Breakdown of land by type of occupation in mainland France in 2015 (Mha: million hectares), and net annual change. Each year, between 2006 and 2015, an average of 66,000 hectares of land were artificial. Two-thirds of this expansion of artificialized land is at the expense of agricultural land, which is explained by the fact that more is being built in the plains and in peri-urban areas, where agriculture dominates. It therefore enters into direct competition with agricultural activities linked to short supply chains and local food (such as market gardening). Source: Les Greniers d´Abondance, after Agreste (2017).

The artificialization continues today at a sustained pace. The equivalent of the average surface of a French department disappears under human constructions every 10 to 15 years. If nothing is done to curb the trend, the surface area of artificialized soils will increase by a third in the next decade . 280,000 hectares of additional natural and agricultural spaces would then be artificialized by 2030, a little more than the area of Luxembourg.

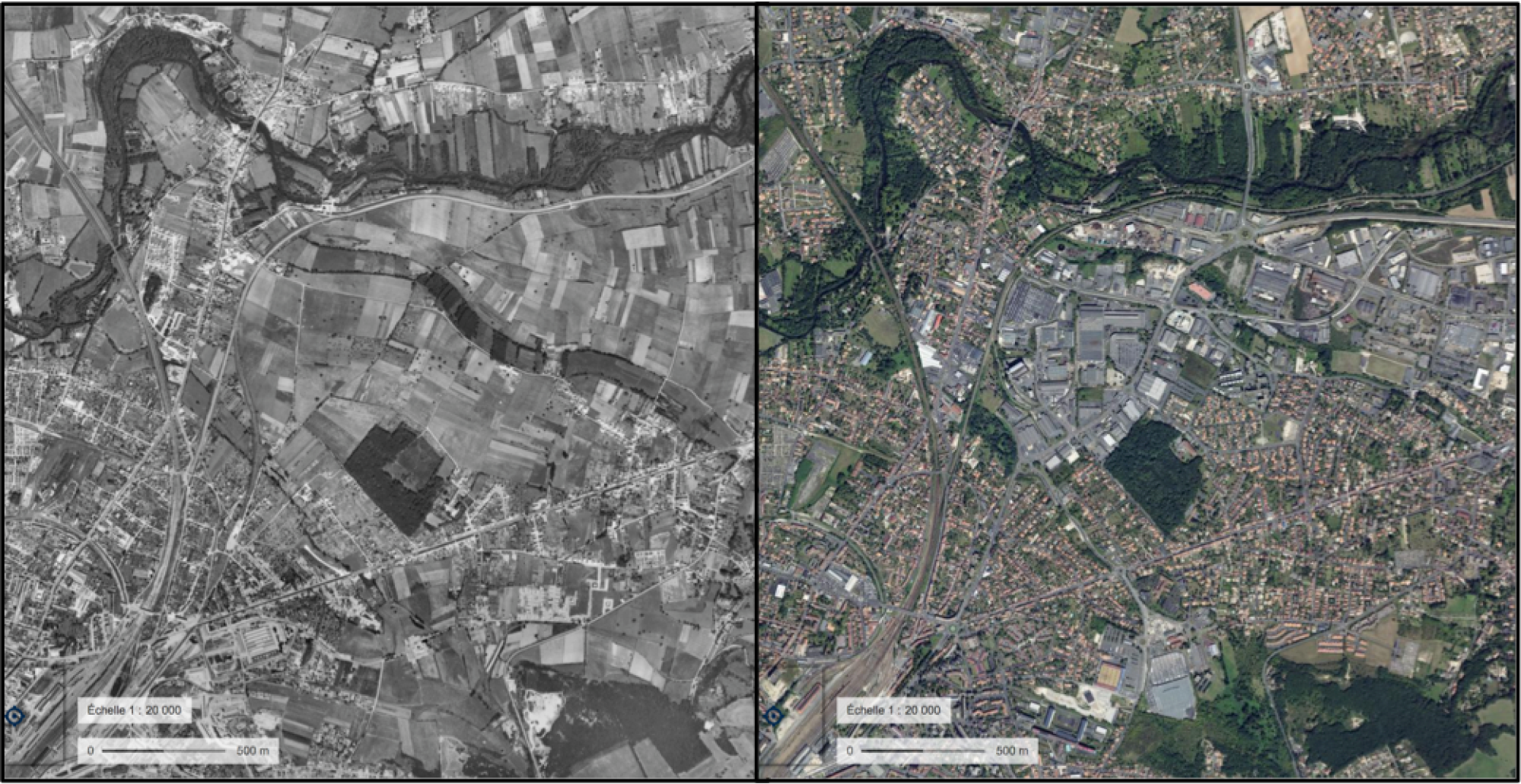

Aerial views of the northeastern sector of Angoulême (Charente), in 1960 (left) and 2018 (right). Several hundred hectares of fertile land have been converted into residential areas, logistics areas and commercial areas. Crédits : IGN, Remonter le temps.

Urban sprawl, the main culprit

Relative to the population, the rate of artificialization in France is well above the European average. Contrary to popular belief, the disappearance of agricultural land is not the inevitable consequence of population growth. Artificial land is growing three times faster than the French population (Figure 16) . Internal migration and access to housing are not the main culprits for this phenomenon either: according to a ministerial report on the artificialization of soils, 70% of this occurs in areas without market tension. housing. According to the same report, 40% of artificialization takes place where the vacancy of housing increases strongly . In France, nearly one in ten homes is vacant, without taking into account second homes!

Figure 16 : Comparative changes in the artificial surface area and the French population between 2006 and 2015 (base 100 in 2006). Artificialization is progressing three times faster than demography. Source : Commissariat Général au Développement Durable (2018b).

The growth of artificialized land finds its origins above all in urban sprawl : sprawl of peripheral spaces, and multiplication of pockets of rapid artificialization (shopping areas, residential areas). Single-family homes accounted for 51% of additional space consumption between 1992 and 2004, or 2.8 times more than the extension of the road network and 37 times more than collective housing.

Residential development in the northern outskirts of Dijon. The construction of individual dwellings represents more than half of artificialization. Crédits : IGN, Géoportail.

French communities are very far from the "zero net artificialization" (ZAN) objective, however set as an objective by the European Commission in 2011 and included in the 2018 Biodiversity Plan . Already in 2010, the law on the modernization of agriculture and fisheries set a target of halving by 2020 the rate of artificialization of agricultural land. The various laws that have tried for twenty years to limit peri-urbanization through town planning documents (SRU laws 2000, Grenelle II 2010, ALUR 2014) have not succeeded in curbing this phenomenon significantly.

Quels liens avec la résilience ?

Associated threats: climate change, soil degradation and artificialization

The main settlements have historically been concentrated in the midst of fertile agricultural land, on which they depended for their food before the massive development of road transport. Urban sprawl therefore primarily affects the richest lands, and located in the immediate vicinity of where people live : cereal basins, silty valleys, market garden lands ...

The continued urban expansion of recent decades has made it difficult for landlords to lease their land on the outskirts of cities to farmers, for fear of not being able to get it back when it becomes constructible. This phenomenon of land retention is unfavorable to local agriculture and is at the origin of the fallow of many quality agricultural land .

Nationally, the available agricultural area per capita has halved since 1930 due to population growth and the decline in cultivated land. It increased from 8,300 m² per capita in 1930 to 4,400 m² in 2017. By way of comparison, the area required to satisfy the current average diet in France is around 4,000 m² per capita. Faced with the uncertainties weighing on our ability to maintain high yields, maintaining a maximum of productive agricultural land is obviously a key element of resilience.

The forms of development associated with the consumption of space, in the first place of which single-family housing, induce a strong dependence on private cars for work and for food. Urban sprawl increases the average distance to be traveled to shop for food and to get to work, thus increasing dependence on oil.

Finally, the artificialization of soils prevents the infiltration of rainwater, thus limiting the recharge of groundwater and increasing both the risk of droughts and floods.

Objectives

Responsible for land use planning, local communities have a direct role in the preservation of natural and agricultural areas. Their mission is to link agriculture with other regional issues: policies related to employment (economic development plan), planning and mobility (local urban planning, urban travel plan), energy (Climate Plan), or the protection of water and biodiversity (Green and blue networks, Water development and management plan).

It is a question of reversing the gaze focused on natural, agricultural and forest areas, usually perceived in negative terms of urbanized areas, as virgin territories reserved for potential future urbanization . The process of preparing town-planning documents should therefore start with a diagnosis of the territory's natural resources (natural and agricultural areas, biodiversity), then with their protection with regard to their fundamental role in a context of ecological and climatic upheaval. The issues related to housing or economic activities would then be taken into account by limiting their consumption of space as much as possible: density analysis, identification of hollow teeth, conversion of wasteland, etc.

As France Strategy explains, achieving the "zero net artificialization" objective from 2030 is possible. This requires adopting a coherent development policy following the sequence (1) avoid (2) reduce (3) compensate . It is therefore primarily a question of questioning any development project for non-urbanized spaces, in order to prefer the densification and / or renovation of the existing and, where appropriate, the conversion of urban wastelands.

Communities seeking to contain their urbanization generally take their previous planning documents as their benchmark, and tend to present any slowdown in the flow of artificialization as progress. This comparison is misleading, on the one hand because their previous documents are often very permissive, and on the other hand because it maintains a confusion between stock and flow: a new artificialized space always represents a net loss of natural and agricultural spaces, and therefore an aggravation compared to the initial situation . As we have seen, the current situation is already largely degraded (especially with regard to our European neighbors). Thus, a development policy is only really economical on condition that it does not consume natural or agricultural spaces, or even restore artificialized land to them - for example by restoring urban wastelands.

Actionnable Levers

Many regulatory, tax, land planning or intervention tools exist to effectively protect agricultural land. It is essential that the development policy be part of an "avoid-reduce-compensate" logic , to achieve the objective of "zero net artificialization" (ZAN).

LEVER 1 : Observe agricultural land to know and limit its artificialization

- Carry out an inventory of land that can be mobilized for agricultural activities , which can be integrated into a Territorial Food Project (PAT) or a Territory Project for Water Management. The actors who can be mobilized include the town planning services, SAFER, associative networks (for example Terre de Liens and its Earth Watchers), and field actors (river technicians, Natura 2000 coordinators, sector technicians from professional agricultural organizations, local elected officials, etc.).

- Set up and finance a land monitoring system , for continuous monitoring of the land situation. This requires animation and cartographic tracking tools.

The Observatoire National de l’Artificialisation developed under the Biodiversity Plan provides a very complete set of databases on artificialization and land use.

LEVER 2 : Protecting farmland

Beyond the drastic limitation of areas open to urbanization in town planning documents, regulatory tools for the protection of land that go beyond the short-termism of electoral mandates must be put in place in the urban periphery to stop speculation and retention land, and sustainably protect agricultural land:

- the protected agricultural zones (ZAP) are public utility easements established by prefectural decree, at the request of the municipalities. They are annexed to the town planning document, to which they are binding. are intended for the protection of agricultural areas the preservation of which is of general interest because of the quality of the productions or the geographical location.

- perimeters for the protection of peri-urban agricultural and natural spaces (PAEN) are established by the department with the agreement of the municipalities concerned and on the advice of the chamber of agriculture, after a public inquiry . A contribution of the PAEN compared to the ZAP is to integrate a territorial agricultural project, in order to support the activity and possibly to orient it towards local food.

In 2010, the municipalities of Canohès and Pollestres (Pyrénées-Orientales) mobilized an innovative tool: the perimeter for the protection and enhancement of peri-urban agricultural and natural spaces (PAEN). This device makes it possible to durably protect the natural and agricultural landscapes in the Prade sector (in green) and the adjoining plateau (in red), threatened by urban sprawl and agricultural decline. Crédits : Terre de Liens (2018).

LEVER 3 : Concentrate development within spaces that are already artificialised

Stop residential construction (the main cause of artificialization) and the extension of peripheral commercial zones . Replace these arrangements with:

- The renewal and rehabilitation of the vacant housing stock;

- The BIMBY approach (Build in my backyard): support for landowners in the cadastral division to densify garden funds.

Establish space-saving urban planning documents, fixing :

- a density floor for the new developed spaces (minimum land use coefficient);

- a floor rate of urban reinvestment for the construction of housing and other buildings.

Implement a trade and economic policy favoring :

- Investment in centralities (towns and villages) instead of shopping areas and peripheral business parks;

- The conversion of commercial and industrial wasteland to develop new activities;

- If necessary, study the budgetary and technical revision of space-consuming development operations to interrupt unrealized development phases.

Building an incentive tax system :

- To promote the renovation and use of the existing housing stock, introduce a tax on vacant housing, and contact owners via the operators of the National Housing Agency to offer assistance for renovation, or the “affordable rental” scheme;

- Municipalities can set up a “payment for sub-density” in urbanized (U) and to be urbanized (AU) areas, with the setting of a minimum density threshold by the municipal council, to encourage planners to save space and densify the layout;

- Agricultural land can also be partially or totally exempt from the municipal part of the property tax on non-built properties.

LEVER 4 : Achieving zero net artificialization

This is to renature an existing artificial surface equivalent to the new built surfaces. This notably involves deconstruction, depollution, waterproofing, construction of technosols allowing revegetation and functional reconnection to the surrounding natural ecosystems.

However, these compensatory measures are complex and costly, and some effects of artificialization are in practice irreversible. Its cost would fluctuate between 1.9 and 2.3 million euros per hectare. Compensation cannot therefore constitute the heart of a "zero net artificialization" strategy .

Side Benefits

Stopping the artificialization of land helps to safeguard biodiversity and landscapes. This reduces the risk of flooding and urban heat island phenomena.

The end of urban sprawl facilitates the establishment of public transport networks, reduces home / work distances and dependence on private cars. This revitalizes city centers and towns, while limiting the need for new infrastructure and its weight on local finances.

Obstacles

Shortfall for landowners One hectare of farmland that becomes constructible may be enough to make their owner a millionaire. It is then for the municipalities to make these lands permanently non-constructible in order to limit speculation on their future, for example through specific protections (ZAP and PAEN). This requires real political will, but also broad consultation to promote acceptance of these measures. The question is sensitive when it comes to farmers: very low pension levels can encourage taking the opportunity when the valuation of the property is important. Acting on farmers' pensions at the national level would facilitate the preservation of agricultural land.

Social acceptability The social acceptability of planning policies is at the heart of the concerns of communities. Even if densification policies are part of a logic of preserving common goods (natural, agricultural and forest areas), their implications on lifestyle are not necessarily acclaimed by the majority. However, the renovation of the city center or the rehabilitation of wasteland should be viewed very positively.

Tax laws not incentivising

The current tax system was not designed in terms of incentives to limit the "consumption" of land, but with a view to financing equipment or other policies. The rate of the municipal or inter-municipal part of the development tax may be increased (up to 20%) in sectors requiring the realization of substantial road works or networks. If we think in terms of full cost, urban sprawl leads to a significant increase in spending on equipment and public services for communities, but the current tax system compensates for the dissuasive nature of this spending. Taxation should therefore be reviewed in order to encourage restrictive zoning, the densification of existing areas and the rehabilitation of wasteland.

Communal planning

Today, the governance of planning is still largely communal, although this competence in theory falls to intercommunalities. This can be an obstacle when the interests of the municipalities and the ambitions of the EPCIs diverge.

Indicators

- Artificial surface area per year and per inhabitant

- Artificial surface per household and job hosted

- Rate of retail space per inhabitant

- Evolution of the number of vacant housing and commercial premises in centralities (towns and villages)